Table of Contents

Introduction

Substack.com declines to moderate political speech.

We believe that supporting individual rights and civil liberties while subjecting ideas to open discourse is the best way to strip bad ideas of their power. We are committed to upholding and protecting freedom of expression, even when it hurts.

Substack.com confuses its role in providing a writing platform with the restrictions on the state in prior restraint of speech. Substack.com has a flawed view of the marketplace for ideas. Its stance will lead to the degradation of the writing platform's usefulness. But does it matter and what should be done?

Defined terms

When I use a word … it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less. Charles Lutwidge Dodgson

Contra:

Nor do the definitions or explanations wherewith in some things learned men are wont to guard and defend themselves, by any means set the matter right. Francis Bacon

I use these terms throughout with the meanings given below.

Nazi, as an adjective, is synonymous with fascist and emblematic of authoritarian rule with the following features:

- a leadership commanding rather than representing

- a unified community based on ties of blood and soil (and rejecting and degrading those who are not of the community)

- coordination and propaganda

- support for at least some traditional hierarchies

- hatred of socialists and liberals and—almost always—

- hatred of “rootless cosmopolites,” [meaning Jews]

Bullet points from: DeLong, J. B. (2023). Slouching towards utopia: An economic history of the Twentieth Century. Basic Books.

Political speech for my purpose consists of writing on topics concerning public policy and governance, whether, for example,

- the United States should/should not withdraw from international treaties recognizing rights of asylum

- the Constitution should/should not be amended to guarantee rights of personal bodily autonomy respecting pregnacy

- the State of Idaho should/should not forcibly annex Washington and Oregon counties lying east of the Cascade Mountains

- a better organized and executed intervention by force to prevent certification of the Presidential Election of 2024 should/should not be undertaken

- specific people identified as enemies of the state should/should not be apprehended, tried, and punished by self-appointed citizen tribunals

- the perfidious [insert disfavored minority] should/should not be expelled from the country, regardless of birth or citizenship to purify the American people, as a first step to reversing the pollution of the true American race

Restraint of political speech consists for my purpose in removing political speech based viewpoint. Restraint does not mean requiring prior approval of posts (censorship). When termed “moderation”, it is action taken by Substack.com as writing platform provider to remove a post in its entirety only or to revoke posting privileges, not to require editorial revision.

State actors are units of government are distinguished by their ability, consistent with law, to coercively impose their will.

Private actors are persons, including natural persons and non-state legal entities, distinguished from state actors in having solely those restrictions or obligations that are imposed upon them by law or that are agreed to by them.

Substack.com means the platform provider, substack (lowercased) refers to the association of writers and readers on Substack.com.

Argument

Substack.com is not a state actor

No law requires Substack.com to accept content from any or all writers. The New York Times does, from time to time, publish letters from readers, but is not obligated to. Likewise, no law prohibit Substack.com from restraining political speech. Substack.com's content guidelines proscribe several types of speech; however, varieties of political speech, per se, are not among them.

Nevertheless, the application of the rationale against state actor restraint on political speech possibly informs the private actor case

Modern rationale for limitation of state actor power over political speech

A state actor with the power to control political speech has the power to dictate the terms of public debate and thereby potentially maintain its officials in power.

Early history of state actor power over political speech

In Europe before the introduction of movable type printing around 1450, widely available written materials were not part of political discourse, which was conducted in person or by private correspondence among the small percentage of the literate population and limited by the even smaller percentage of that population having a say in goverance. In England, estimated consumption of written material in manuscript form has been estimated at 0.5 manuscripts per thousand population. From 1450, the estimated consumption of written material in the form of printed books there grew from 2 per thousand population to nearly 200 per thousand by 1800.

William Caxton returned to England from Europe in the early 1470s to set up as a printer and then was followed by European printers. The first press in England was a free press that was extended special privileges not allowed other aliens

Provided always that this act or any parcel thereof, or any other act made, or to be made in this said parliament, shall not extend, or be in prejudice, disturbance, damage, or impediment, to any artificer, or merchant stranger, of what nation or country he be, or shall be of, for bringing into this realm, or selling by retail, or otherwise, any books written or printed, or for inhabiting within this said realm for the same intent, or any scrivener, alluminor, binder or printer of such books, which he hath, or shall have to sell by way of merchandise, or for their dwelling within this said realm, for the exercise of the said occupations; this act or any part thereof notwithstanding. 1 Ric. 3 c.9 An Act touchinge the Marchaunts of Italy (1484).

In 1534, however, An Act for Printers, and Binders of Books, 1534, 25 Hen.VIII, c.15. subordinated the printing industry to the King's Great Cause. It was part of a comprehensive program of legislation designed to secure the power of Henry VIII over the Church of England, newly removed from the Catholic Church. It provided for the licensing of printing, which required a separate approval for each book or pamphlet after review by the authorities. In contrast to the occasional earlier supression of books and manuscripts on purely religious grounds, in the English Reformation religion and politics were inseparable. In the Anglo-American tradition, this is the best example of restraint on political speech. Violations were referred to the Star Chamber. A typesetting error that omitted the word “not” from the Seventh Commandment cost one printer a fine of £3,000 (on the order of £15,000,000 today in terms of income).

The rising political tensions between Charles I and Parliament from his accession in 1625 led to his dissolving Parliament in 1629 for 11 years. A very detailed implementing decree of the Star Chamber in 1637 issued covering all aspects of print, including licensing of type foundries, which were limited to only four, and prior review of all books and pamphlets. The crown asserted control of every aspect of publishing. In 1641, Parliament abolished the Star Chamber, which effectively deregulated the press. A surge in publication followed, which Parliament attempted to address piecemeal.

Because three interim ad hoc orders had failed adequately to control

… great late abuses and frequent disorders in Printing many false, forged, scandalous, seditious, libellous, and unlicensed Papers, Pamphlets, and Books to the great defamation of Religion and Government

Parliament brought back even more stringent press control with the The Licensing Order of 1643, a year into the First English Civil War. It granted a monopoly to the Company of Stationers and charged it to censor all printing. The new restrictions were even more all-encompassing than the Royal controls they replaced. John Milton objected in the following year with Areopagitica; A Speech of Mr. John Milton for the Liberty of Unlicenc'd Printing, To the Parlament of England. (He neglected to comply with the requirements of the new law when he published it.)

Milton raised four principal objections:

1. Reading material thought to contain harmful ideas would be fully as likely to lead to its rejection as to its acceptance

2. It would fail in its object to suppress the harmful effects of unlicensed material

3. It would hinder the spread of helpful new ideas as much or more than harmful ideas

4. The effort required effectively to conduct pre-publication review would be greater than could be expected to actually occur

Returning to a more relaxed approach to regulation would, he argued, still leave open prosecution post-publication. Continuing the requirement that the author's and printer's name be registered

if they be found mischievous and libellous, the fire and the executioner will be the timeliest and the most effectual remedy that man's prevention can use

Milton was not a free speech absolutist. Allowing publication to proceed without review did not also protect against punishment by death. He would also silence those whose errors could not be gently reformed

I mean not tolerated Popery, and open superstition, which, as it extirpates all religions and civil supremacies, so itself should be extirpate, provided first that all charitable and compassionate means be used to win and regain the weak and the misled

His theatre of discourse admitted only those who could agree to disagree in a mutual search for truth, albeit only consistently with at least the major outlines of his commitment to the Reformation. He had no truck with speech aimed at completely overthrowing the existing order by, for example, restoring Papal supremacy.

Parliament was not persuaded and the Licensing Act of 1643 remained in effect throughout the English Civil Wars, the Commonwealth and into the Restoration. Charles II persuaded Parliament to go further with An Act for preventing the frequent Abuses in printing seditious treasonable and unlicensed Books and Pamphlets and for regulating of Printing and Printing Presses (4 Cha. 2. c. 3). It provided for a single licensed newspaper, and its management was to have pre-approval of all other printing.

The follow-on Licensing of the Press Act 1662 was in effect off and on through 1695, when it expired by its terms. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the Bill of Rights of 1688 had only one thought concerning political speech

That the freedom of speech and debates or proceedings in Parliament ought not to be impeached or questioned in any court or place out of Parliament

The association of the restrictive press laws on the availability of printed matter can be seen in the figure above, showing a decline between estimates for 1650 and 1700 mid-way through which English law no longer required the prior restraint of licensing, when a recovery can be seen. What remained of press regulation including following Milton's suggestion to seek out offensive writings post-publication. Warrants would issue to search premises for evidence of authorship of articles thought seditious by the Government. The most famous is

George Montagu Dunk, Earl of Halifax, Viscount Sunbury, and Baron Halifax, one of the Lords of His Majesty's Honourable Privy Council, Lieutenant-General of His Majesty's Forces, Lord Lieutenant-General and General Governor of the kingdom of Ireland, and principal Secretary of State, etc. These are in His Majesty's name to authorize and require you, taking a constable to your assistance, to make strict and diligent search for John Entick, the author, or one concerned in the writing of several weekly very seditious papers, intitled The Monitor, or British Freeholder, No. 357, 358, 360, 373, 378, 379, 380; London, printed for J. Wilson and J. Fell in Paternoster-Row; which contain gross and scandalous reflections and invectives upon His Majesty's Government, and upon both Houses of Parliament, and him having found, you are to seize and apprehend, and to bring, together with his books and papers, in safe custody before me to [b]e examined concerning the premises, and further dealt with according to law; in the due execution whereof all mayors, sheriffs, justices of the peace, constables, and other His Majesty's officers civil and military, and loving subjects whom it may concern, are to be aiding and assisting to you as there shall be occasion; and for so doing this shall be your warrant. Given at St. James's the 6th day of November 1762, in the third year of His Majesty's reign. Dunk Halifax. To Nathan Carrington, James Watson, Thomas Ardran, and Robert Blackmore, four of His Majesty's messengers in ordinary. Entick v Carrington & Ors [1765] EWHC KB J98

The Court of King's Bench held the warrant illegal and sustained a verdict of trespass, even while agreeing with the substance, while not the conclusion, of defendant's argument

Supposing the practice of granting warrants to search for libels against the State be admitted to be an evil in particular cases, yet to let such libellers escape who endeavour to raise rebellion is a greater evil

In colonial America, similar writs of assistance (decried as “roving warrants” because they empowered search for evidence of tax evasion where the collectors thought they might be found) were abused to search private papers for evidence of brewing political discontent.

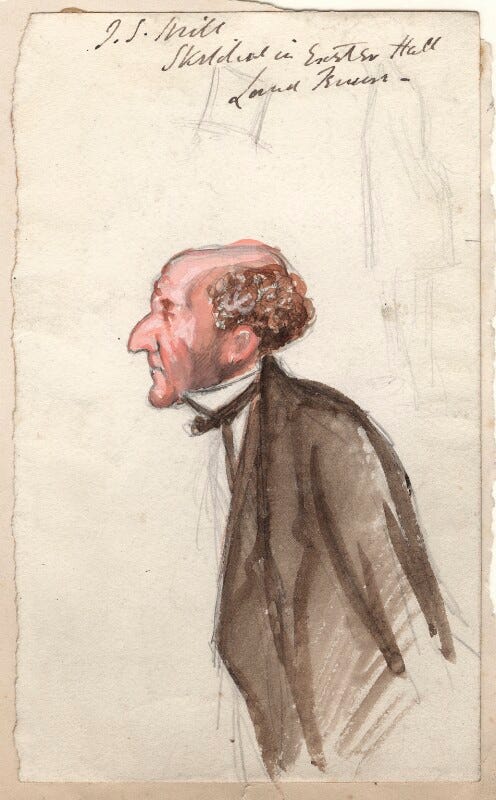

By 1859, John Stuart Mill in his extended essay On Liberty observed that while the forms of state actor control over political speech remained

there is little danger of its being actually put in force against political discussion, except during some temporary panic, when fear of insurrection drives ministers and judges from their propriety

Mill goes beyond Milton in taking a strong position in favor of speech unconstrained by state actors, but principally his arguments bear more on private actors.

We have now recognised the necessity to the mental well-being of mankind (on which all their other well-being depends) of freedom of opinion, and freedom of the expression of opinion, on four distinct grounds; which we will now briefly recapitulate.

The first three are philosophical, dealing with how best to find truth. Mill presupposes that truth exists and is determinable through the exchange of opinion. Those are strong assumptions.

First, if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility.

Secondly, though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions, that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied.

Thirdly, even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is, vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension or feeling of its rational grounds. …

The fourth is the salutary effect of keeping received truth freshened through continued examination

… And not only this, but, fourthly, the meaning of the doctrine itself will be in danger of being lost, or enfeebled, and deprived of its vital effect on the character and conduct: the dogma becoming a mere formal profession, inefficacious for good, but cumbering the ground, and preventing the growth of any real and heartfelt conviction, from reason or personal experience.

Next, he addresses moderation of discourse. He first deals with intemperate expression

Before quitting the subject of freedom of opinion, it is fit to take some notice of those who say, that the free expression of all opinions should be permitted, on condition that the manner be temperate, and do not pass the bounds of fair discussion. Much might be said on the impossibility of fixing where these supposed bounds are to be placed; for if the test be offence to those whose opinion is attacked, I think experience testifies that this offence is given whenever the attack is telling and powerful, and that every opponent who pushes them hard, and whom they find it difficult to answer, appears to them, if he shows any strong feeling on the subject, an intemperate opponent. But this, though an important consideration in a practical point of view, merges in a more fundamental objection. Undoubtedly the manner of asserting an opinion, even though it be a true one, may be very objectionable, and may justly incur severe censure. But the principal offences of the kind are such as it is mostly impossible, unless by accidental self-betrayal, to bring home to conviction.

He then discusses argument in violation of the norms of honest debate whether propounded by those who should know better or by fools, assuming that either is sincere

The gravest of them is, to argue sophistically, to suppress facts or arguments, to misstate the elements of the case, or misrepresent the opposite opinion. But all this, even to the most aggravated degree, is so continually done in perfect good faith, by persons who are not considered, and in many other respects may not deserve to be considered, ignorant or incompetent, that it is rarely possible on adequate grounds conscientiously to stamp the misrepresentation as morally culpable; and still less could law presume to interfere with this kind of controversial misconduct.

The closing observation that the state should not interfere discounts his very first claim that there is little reason that it would "except in times of panic." Mill's argument should be read to regulation by private actors, such as Substack.com,

Finally, he deals with intemperate discourse

With regard to what is commonly meant by intemperate discussion, namely invective, sarcasm, personality, and the like, the denunciation of these weapons would deserve more sympathy if it were ever proposed to interdict them equally to both sides; but it is only desired to restrain the employment of them against the prevailing opinion: against the unprevailing they may not only be used without general disapproval, but will be likely to obtain for him who uses them the praise of honest zeal and righteous indignation. Yet whatever mischief arises from their use, is greatest when they are employed against the comparatively defenceless; and whatever unfair advantage can be derived by any opinion from this mode of asserting it, accrues almost exclusively to received opinions. The worst offence of this kind which can be committed by a polemic, is to stigmatise those who hold the contrary opinion as bad and immoral men. To calumny of this sort, those who hold any unpopular opinion are peculiarly exposed, because they are in general few and uninfluential, and nobody but themselves feel much interest in seeing justice done them; but this weapon is, from the nature of the case, denied to those who attack a prevailing opinion: they can neither use it with safety to themselves, nor, if they could, would it do anything but recoil on their own cause. In general, opinions contrary to those commonly received can only obtain a hearing by studied moderation of language, and the most cautious avoidance of unnecessary offence, from which they hardly ever deviate even in a slight degree without losing ground: while unmeasured vituperation employed on the side of the prevailing opinion, really does deter people from professing contrary opinions, and from listening to those who profess them. For the interest, therefore, of truth and justice, it is far more important to restrain this employment of vituperative language than the other; and, for example, if it were necessary to choose, there would be much more need to discourage offensive attacks on infidelity, than on religion. It is, however, obvious that law and authority have no business with restraining either, while opinion ought, in every instance, to determine its verdict by the circumstances of the individual case; condemning everyone, on whichever side of the argument he places himself, in whose mode of advocacy either want of candour, or malignity, bigotry, or intolerance of feeling manifest themselves; but not inferring these vices from the side which a person takes, though it be the contrary side of the question to our own: and giving merited honour to everyone, whatever opinion he may hold, who has calmness to see and honesty to state what his opponents and their opinions really are, exaggerating nothing to their discredit, keeping nothing back which tells, or can be supposed to tell, in their favour. This is the real morality of public discussion; and if often violated, I am happy to think that there are many controversialists who to a great extent observe it, and a still greater number who conscientiously strive towards it.

In this view, the objection to discourse on the grounds of its offensiveness fails due to the lack of application independent of viewpoint. The suppression of unpopular opinion only while finding equally obnoxiously expressed popular opinion unobjectionable is problematic. Even when applied evenhandedly, however, it fails when a disfavored viewpoint expressed with temperance is condemned by association with the same beliefs expressed vilely. He seems content in the expectation that meritless, disruptive advocacy will fail in its aim to convince and fall by the wayside.

However, Mill admits that intellectual rigor is not always to be expected because

… in proportion to a man’s want of confidence in his own solitary judgment, does he usually repose, with implicit trust, on the infallibility of “the world” in general. And the world, to each individual, means the part of it with which he comes in contact; his party, his sect, his church, his class of society: the man may be called, by comparison, almost liberal and large-minded to whom it means anything so comprehensive as his own country or his own age. Nor is his faith in this collective authority at all shaken by his being aware that other ages, countries, sects, churches, classes, and parties have thought, and even now think, the exact reverse. He devolves upon his own world the responsibility of being in the right against the dissentient worlds of other people; and it never troubles him that mere accident has decided which of these numerous worlds is the object of his reliance, and that the same causes which make him a Churchman in London, would have made him a Buddhist or a Confucian in Pekin.

Throughout, Mill conflates truth with values. As applied to political speech the idea that truth and political choices can be determined identically is fatally flawed. The realm of politics is not truth but values. Politics ought not have the same aim as religion. We justly suspect that when theocracies claim that obedience to the word of God is due, what is actually meant is submission to the word of the state. Politics is, rather, the search for collective agreement on what to do together. There is no truth inherent in the choice between an appropriation of $50 billion and one for $40 billion so that the difference might be applied to a different purpose also worthy of attention. There is no truth involved in allowing accelerated depreciation schedules for favored types of business capital investment. There is, at most, the opportunity for debate as to means and ends. Will the scheme effectuate the ends? Are the ends valuable?

Finally, Mill introduces the argument from economic efficiency, the standard of classical economic liberalism, the objective arbitration of the marketplace.

But it is now recognised, though not till after a long struggle, that both the cheapness and the good quality of commodities are most effectually provided for by leaving the producers and sellers perfectly free, under the sole check of equal freedom to the buyers for supplying themselves elsewhere. This is the so-called doctrine of Free Trade, which rests on grounds different from, though equally solid with, the principle of individual liberty asserted in this Essay.

The Marketplace of Ideas

This formulation of the justification for free speech was replanted in American soil where it has continued to flourish over the past 70 years as a foundation of First Amendment jurisprudence.

Like the publishers of newspapers, magazines, or books, this publisher [a pamphleteer] bids for the minds of men in the market place of ideas. The aim of the historic struggle for a free press was "to establish and preserve the right of the English people to full information in respect of the doings or misdoings of their government." Douglas, J. concurring, United States v. Rumely, 345 U.S. 41 (1953)

Mentions of the marketplace of ideas in the Supreme Court's decision in the most recent major First Amendment case, Citizens United included

prevent corporations from obtaining an unfair advantage in the political marketplace by using resources amassed in the economic marketplace … the open marketplace of ideas protected by the First Amendment. … will choose simply to abstain from protected speech — harming not only themselves but society as a whole, which is deprived of an uninhibited marketplace of ideas … they would help citizens … informed choices in the political marketplace … an unfair advantage in the political marketplace … threat to the political marketplace … may compete in this marketplace without government interference … the corrosive and distorting effects of immense aggregations of wealth in the marketplace of ideas … the integrity of the marketplace of political ideas … repetitive speech in the marketplace of ideas … some breathing room around the electoral marketplace of ideas … the marketplace in which the actual people of this Nation determine how they will govern themselves … the marketplace of ideas is not actually a place where items — or laws — are meant to be bought and sold, and when we move from the realm of economics to the realm of corporate electioneering, there may be no reason to think the market ordering is intrinsically good at all … . (opinion of the Court with concurrences and dissents included, quotation marks omitted and emphasis added) Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010)

Justice Stevens, joined by Justices Ginsberg, Breyer and Sotomoyor, in dissent cite Strauss, Corruption, Equality, and Campaign Finance Reform, 94 Colum. L.Rev. 1369 (1994).

Criticism of Market Idolatry

The place in American thought around the virtue of the marketplace as a sort of universal solvent to all ills is secular orthodoxy. In addition to the promoting of the fruitful exchange of ideas, through an invisible hand of the market the market for goods and services promotes

- Self-regulation through the laws of supply and demand that balance through the price mechanism

- The pursuit of individual values promotes, in the aggregate, the social good

- Decisions are vested in the individual

- Optimal allocation of resources

- Markets lead to Pareto-optimal outcomes

Markets do not self-regulate

While supply and demand can be brought into alignment through the market clearing properties of price signaling, more is required to constitute a market. Market transactions do not occur in the imagined void in which only the principals participate. Markets have social and political structure; otherwise, transaction costs would be too high. Transactions may be in kind or effected by currency, most often fiat currency because it has the greatest liquidity and lowest costs of settlement. Public law makes enforceable party autonomy in shaping and enforcing contracts. For example, without intellectual property law to prevent buyers from competing against sellers using the seller's own property, no one would transact business in intellectual property. The essence of a property right is the right to exclude. Marketplaces must be secure for obvious reasons.

Even within the sphere of economic activity, organizations do not conduct internal operations through market mechanisms. Coase, R.H. (1937), The Nature of the Firm. Economica, 4: 386-405.

The sum of the parts is not held in common

Market transactions are a zero-sum game. Although market transactions close at the clearing price the value of the subject matter is not, thereby, frozen. Values are volatile and at any point in the future one party or the other has possession of that value at a gain or loss over basis. There is no win-win.

Hence the Wall Street adage—there is a fool in every deal, and if you can't spot who it is around the closing table then it's you. As corrollaries, it is the aggregate of individual utility that is maximized, but there is little likelihood that utility will be evenly distributed and even less likelihood that the common good will be enhanced. Benthamite utilitarianism is neither a goal nor an outcome of market mechanisms—the market may tend not to the greatest good for the greatest number but rather to the greatest good for the least number. Commodity markets may tend to a normal distribution of outcomes but many markets are fat tailed due to information arbitrage, lack of competition, network scale effects and scale-free effects as well as winner take all outcomes.

Optimality is limited by bounded rationality

In the classical view economic actors, whether individuals or fictive persons, are assumed to act in their self-interest with a view toward the maximization of value according to some objective utility function that can be independently calculated with identical results. Interest group liberalism is the political counterpart to the claimed tendency of markets to maximize good. In the political case, the public interest is deemed to be the aggregate interests of separate groups. The concept misses a parallel with the market model for lack of a weighting mechanism. Every interest group wants to be special but hopes to avoid being considered a special interest group and thereby less deserving of political consideration. Furthermore, it does not account for interests unrepresented in the debate.

However, except in computable cases, strict rationality is not observed in the wild. The classical model of economic rationality abtracts away human psychology. Cognitive biases and the burden of sustained rationale problem solving under uncertainty lead to short cuts in thinking and the application of idiosyncratic, non-reproducible intuition and emotion to choice. See Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty.” Science 185.4157 (1974): 1124-1131 (Kahneman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for his work in 2002 and remains the only psychologist to be so recognized.) The information available and missing and the time in which to evaluate it lead to satisficing (making good enough), not optimizing behavior due to bounded rationality. Herbert A. Simon, Models of Man, New York: John Wiley 1957.

Caveat emptor

The notion of a fair market price is what a willing seller and willing buyer would agree to if neither were under duress. The scope of individual market autonomy is limited outside markets in which sellers and buyers have parity of bargaining power. Conditions of perfect competition in which evenly held power exists do not often appear. Sellers may have the ability to extract prices higher than would prevail in the presence of more sellers. Sellers eagerly seek to be able to extract rent through methods such as innovation, marketing, patents, acquisition of competitors, monopoly or oligopolistic combination in restraints of trade and othjer unfair methods of competition contrary to laws that, although governing such conduct, are in disuse and weakly enforced. They exhibit market power by being able to operate under “take it or leave it” contracts of adhesion that are offered on a non-negotiable basis. The buyer has only the two options and may also lack a market substitute.

Is there a property interest in ideas?

A large and growing part of contemporary economic activity consists in transactions in intellectual property. A streaming service pays a licensing fee to an entertainment company for content and sub-licenses that content to a consumer for a fee. What is the property interest in political ideas? Ideas that do not qualify as intellectual property are public goods. The consumption of an idea by one person does not reduce the availability to another. No one can soak up all the street lighting and there is no property interest in it. Why apply a market metaphor to transactions that don’t even involve property at all?

Power

The marketplace of ideas is also the marketplace of power in which one currency is political speech. Other currencies are votes, money, logrolling, backscratching, pork barrelling and violence and threats of violence, among other tokens.

Above all else a marketplace cannot operate without reciprocal exchange of value. For a publishing writing platform, such as Substack.com, participants must at least entertain the possibility of adopting viewpoints encountered, for the sake of argument if nothing else. The epistemologically closed, the ideologues (with adamantine refusal to consider the possibility that the viewpoint they advocate may be flawed) they pollute the marketplace of ideas. Vituperation in exchange for reasoned criticism is not a tenable bargain.

Analysis based on associational freedom

Constitutional law recognizes the right of expressive association as a necessarily adjunct to rights to political speech, assembly and petition protected by the First Amendment and encompassed within the protections of liberty extended by the Fourteenth Amendment. (Overview) There are circumstances under which the Court has upheld state imposition of anti-discrimination requirements against associations. But the Court has also ruled that an association is under no obligation to accommodate expression with which it disagrees. Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston, 515 U.S. 557 (1995) (cited with approval in 303 CREATIVE LLC v. Elenis, 600 U.S. 570 (2023))

While the state may impose reasonable time, place and manner restrictions on political speech in public forums under its operational control not to include viewpoint considerations, it may not do so in political speech by private actors in non-public forums even when the speech is accessible to the public. It can neither require nor prohibit Substack.com from extending posting privileges to Nazi viewpoints.

Tocqueville noted the unique American mode of conducting public debate provided by the multitude (“exceeding all belief”) of local newspapers of small circulation. He also noted a distinct American character of news

The spirit of the journalist in America consists in a crude, unvarnished, and unsubtle attack on the passions of his readers; he leaves principles aside to seize hold of men whom he pursues into their private lives exposing their weaknesses and defects. … personal opinions of journalists carry virtually no weight in readers’ eyes. What the latter look for in newspapers is knowledge of facts; only by altering or distorting these facts can a journalist gain some influence for his views. Democracy in America: And Two Essays on America (Penguin Classics) by Alexis Tocqueville

Eighty years after Tocqueville, the press environment in 1920 and the scope of affairs covered was far different.

The social environment in the communities in which the facts and ideas published in news circulated among a vastly transformed in the three generations (grandparent to grandchild) between 1840 and 1920. The national population grew by five times; the urban population grew by 28 times, while the population nationwide grew only by five times. The urban population grew from less than 10% of the total to more than 50%. The introduction of roll-fed rotary press technology and hot lead typesetting, publishing had low capital barriers to entry. Individual type elements (“sorts,” which became keys in typewriters) and letterpress presses were relatively inexpensive, although labor intensive. Combined with the circulation in small hamlets and neighboring cities, the reach of any idea was limited. Linotype machines and the high-speed offset presses in the early part of the 20th century were capital-intensive. Mechanized production drove down unit per page print costs, opening much space to be filled with reporting and editorial content (“newshole”) and even more for advertising.

Walter Lippmann assessed the state of American journalism in light of the development of news publications of far greater scale by 1920 in terms of public opinion.

… casual opinion, being the product of partial contact, of tradition, and personal interests, cannot in the nature of things take kindly to a method of political thought which is based on exact record, measurement, analysis and comparison. Just those qualities of the mind which determine what shall seem interesting, important, familiar, personal, and dramatic, are the qualities which in the first instance realistic opinion frustrates. Therefore, unless there is in the community at large a growing conviction that prejudice and intuition are not enough, the working out of realistic opinion, which takes time, money, labor, conscious effort, patience, and equanimity, will not find enough support. That conviction grows as self-criticism increases, and makes us conscious of buncombe, contemptuous of ourselves when we employ it, and on guard to detect it. Without an ingrained habit of analyzing opinion when we read, talk, and decide, most of us would hardly suspect the need of better ideas, nor be interested in them when they appear, nor be able to prevent the new technic of political intelligence from being manipulated. Public Opinion by Walter Lippmann

After another two generations, in 1961 Norbert Weiner observed

Thus on all sides we have a triple constriction of the means of communication: the elimination of the less profitable means in favor of the more profitable; the fact that these means are in the hands of the very limited class of wealthy men, and thus naturally express the opinions of that class [who are] ambitious for [political] power. That system which more than all others should contribute to social homeostasis is thrown directly into the hands of those most concerned in the game of power and money … . It is no wonder then that the larger communities, subject to this disruptive influence, contain far less communally available information than the smaller communities, to say nothing of the human elements of which all communities are built up. Cybernetics, Second Edition: or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine by Norbert Wiener

The freedom of association constraints on state actors do not carry over to private actors except in some instances of invidious discrimination. While I might seek to associate with you, you are not required to accept my advance.

Does any of this matter?

Text within this block will maintain its original spacing when publishedAll lies and jest Still a man hears what he wants to hear And disregards the rest, hmm Paul Simon, American songwriter

Nazi political speech on Substack.com is not likely to be a novelty to any existing writer or user, and anyone experiencing it on Substack.com likely has already reached a conclusion. The cumulative degree to which the political speech that Substack.com declines to moderate will affect the outcome of any political is negligable.

Moderating Nazi political speech is not the problem. It's the political system and culture that give Nazi ideas force and effect. Denying free rein to Nazi political speech on Substack.com won't fix that.

Is continuing to write and subscribe on Substack unconscionable?

Does continuing imply endorsement of Nazi political speech? Does withdrawing have any discernible effect? Is it necessary to address the evil of Nazi political speech? Is it sufficient? Does the management of Substack.com deserve condemnation? Do they deserve punishment? Are they misguided or merely venal? Is this the battlefield for 2024? Guilt by association?

Everyone on substack must decide whether it’s a matter of lying down with dogs and getting up with fleas.

What's the ask?

The way that Substack.com has elected to address the problem will fall to Gresham's Law. Nazi political speech will be unfazed by reasoned criticism, is unlikely to persaude readers expecting the standard of discourse that widely prevails on Substack.com and will draw an audience with confirmation bias that will amplify Nazi political speech. Writers wishing to avoid contamination in comments will be required to erect safeguards such as limiting comment to paid subscribers and monitoring carefully the posts of those subscribers, leading to lost opportunities to engage readers in conversations that lead to paid subscriptions or influence opinion. An attack by a swarm of Nazibots will not be feasibly managed by hand.

Substack.com should therefore provide an application programming interfacre (API) to its platform that will permit user easier moderation of which comments are displayed with their writing and what content is displayed on their feed. It should provide methods for both manual and automated processing, including interfacing with AI tools for detection of content that should be filtered out.

Conclusion

Although Substack.com may not be a publisher for purposes of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996, its moderation policy has the same force and effect as editorial judgment. The decision to refrain from moderation of Nazi political speech is an editorial judgment. Substack.com should be held to account in the exercise of its judgment.

How Substack.com exercises its freedom to exclude, admit, or restrict Nazi political speech is within its discretion. Community members who object to the presence of Nazi political speech have no cognizable right of disassociation, their sole option is to depart. Members desirous of making Nazi political speech beyond the other, uncontroversial, limits that Substack,com imposes, such a kiddie porn ban, for example, are equally free to depart.

The marketplace of ideas rationale that Substack.com advances in defense of its policy of letting Nazi political speech escape viewpoint moderation is intellectually vacuous. It is difficult to accept the forum at its claimed value as a venue for thoughtful writing in light of its present policy. It holds itself out this way.

“We are still trying to figure out the best way to handle extremism on the internet. But of all the ways we’ve tried so far, Substack is working the best.” (quoting @Elle Griffin)

It fails to explain how the values it purports to protect, the free expression of political views, are furthered by countenancing the dissemination of political views antithetical to those values on the naïve hope that Nazi political speech will be ignored and go no further. As a platform for many serious writers in the mainstream of political opinion, writers publishing on Substack.com will be able to represent to the credulous that Nazi viewpoints are, themselves, mainstream because otherwise those viewpoints would not be allowed to remain.

The way that Substack.com has elected to address the problem will fall to Gresham's Law. Nazi political speech will be unfazed by reasoned criticism, is unlikely to persaude readers expecting the standard of discourse that widely prevails on Substack.com and will draw an audience with confirmation bias that will amplify Nazi political speech. Writers wishing to avoid contamination of comments will be required to erect safeguards such as limiting comment to paid subscribers and monitoring carefully the posts of those subscribers, leading to lost opportunities to engage readers in conversations that lead to paid subscriptions.

To the extent that Substack.com becomes one of the politically powerful publishing platforms (an implicit consequence of its business ambition) and maintains its absolutist stance to unconstrained political speech, Substack.com will be in part responsible for the transformation of the political regime to self-professed authoritarianism. At that time, it will be too late to hold Substack.com to account whether it intends the extra-judicial state terror to follow. The Revolution Will Not be Televised. Because it will be posted on Substack.com.

The individual decision on whether to leave or stay (Subxit?) comes down to the internal civil war of the prefrontal cortex against the substrates of emotional reaction. It's idiosyncratic and it will be regrettable if a decision comes to be seen as going beyond the question of moderation of political speech to taking sides with the merits or lack thereof of Nazi political speech. It's possible to disagree without the procedural issue without taking a position on the [lack of] merits of the Nazi worldview..